For most children, as soon as they are born they make a sound – a cry. Soon after, they begin to coo and babble, and by about six to eight months they could even start saying words like dada, mama, and bye. Between one and two years old children often string about two words together, sometimes even asking questions like “Where’s puppy?”. By about four to five years old, most neurotypical children can speak clearly about age-appropriate topics, using mostly correct grammar and vocabulary. During this time adults are constantly chatting with their children, giving directions, and explaining the world. In addition, hopefully they are also reading to them before bed, taking them to story time at the library, and helping to “read” the world around them, but children are not yet reading on their own. As you can see, children begin their oral language journey way earlier than their reading journey. Learning to speak is a natural process, but learning to read must be explicitly taught, which usually doesn’t happen until a child begins formal education.

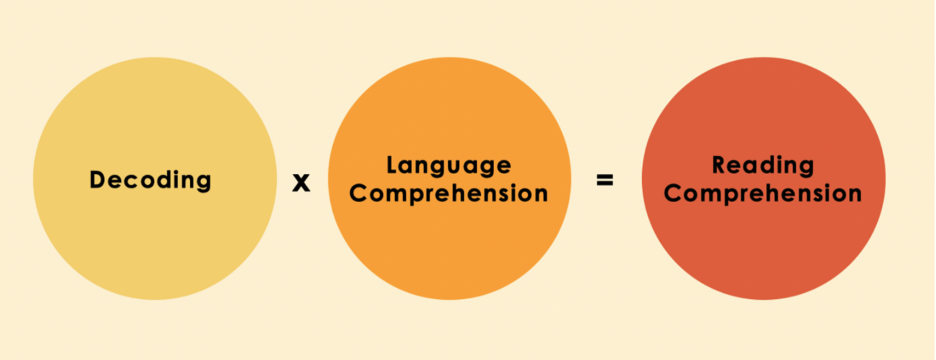

Over 35 years ago, Gough and Tunmer (1986) came up with a framework they called The Simple View of Reading. Their research suggested that reading comprehension is the product of decoding, the ability to transform print into spoken language, and language comprehension, the ability to understand spoken language. In other words if one of these factors is zero or low, your overall reading comprehension will be zero or low, despite the potential for the other factor to be high.

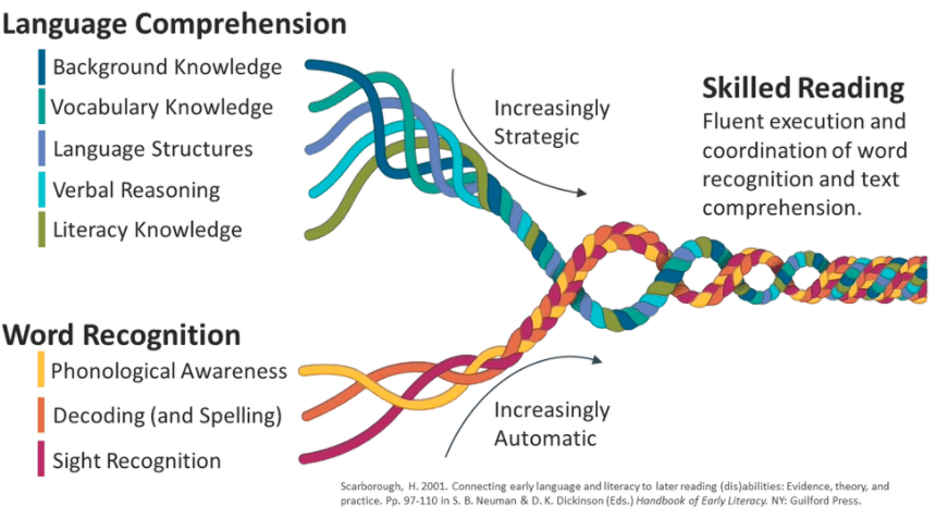

About 15 years later, Scarborough presented her theoretical framework known as Scarborough’s Reading Rope. This broke down The Simple View of Reading into specific categories or strands and showed how they interact with each other. Scarborough’s Rope captures the complexity of learning to read. The strands of the rope start out separated. When children are young, their oral language comprehension skills are usually stronger than their word recognition. They understand stories that are read to them but cannot yet read the words. As they develop word recognition skills and increase their language comprehension, the strands interwine into skilled reading; in other words they can make meaning of text through accurate word reading and understanding.

The above research and theories reinforce the idea that teaching students to read must be explicitly taught. One way teachers do this in the classroom is through specific reading strategies. Strategies provide students with actionable steps, are a means to an end, and offer a temporary scaffold. As a student becomes increasingly automatic, conscious attention to a strategy fades, new reading habits form, and a stronger reader is born!